|

| home | movie reviews | features | sov horror | about | forum |

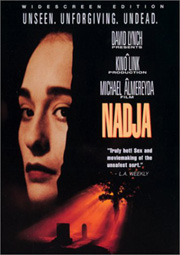

Nadja B

Year Released: 1995

1. There are some blurry mornings when you wake up early, sunlight peeking through the shades, when you feel as though you don't possess the energy or desire to even stand up. You'd rather atrophy under the covers, cloaked from the rigors of daily life. This sensation can also be felt late into the night, in that half-life between sleep and reality. The brain simmers on autopilot and the body is despondent, slow, out of step with the rest of the world. Welcome to the world of the living dead. That's the state of mind the protagonists find themselves in throughout Michael Almereyda's expressionistic modern vampire film, Nadja. They live in a black-and-white nighttown incarnation of New York City. It's filled with lonely people, many desperately holding on to each other for fear of abandonment. This comes in the form of placing family above everything else (as the title character, played by Elina Lowensohn, does in her European party girl interpretation of Dracula's daughter) or in relationships whose affection has drifted toward a comfortably numb period of being taken for granted. Which is not to say that Nadja isn't ironic or funny. Indie would-be auteur Abel Ferrara trapped himself with humorless proclamations about modern society in his unbearable The Addiction (and both films were lumped into the same mid-1990s "East Village Postmodern Deconstructionalist Vampire Film" trilogy as Larry Fessenden's memorably sensual Habit, though each film fulfills the genre requirements in unique and original ways). Almereyda, who understands this horror subcategory so thoroughly he can't help but playfully reference the films of Jean Cocteau and Tod Browning, gently and playfully dances around the conventions. The character that comes across as most vivid and alive in this crowd of zombies and sleepwalking humans is Van Helsing, charismatically embodied in a zesty, long-haired Peter Fonda. Tooling around the streets on his bicycle, dragging his poor nephew Jim (Martin Donovan) in tow, our aging Easy Rider incarnation of Van Helsing spins elaborate yarns about hunting Count Dracula and his bastard children ("He was like Elvis in the end! He was just going through the motions!"). This half-mad vampire hunter is first seen with Jim in a coffee shop wolfing down a chocolate croissant and sipping a coffee, having been just bailed out of prison for shoving a wooden stake through someone's heart. Doesn't anyone know he destroyed an undead fiend? Who needs a drink? Point is, Van Helsing has always had a sense of purpose. This puts him miles ahead of poor Jim, whose relationship with copy shop employee/artist/slacker Lucy (Galaxy Craze, plucked straight from the downtown crowd in her oversized flannel coat and attractive short haircut) is best described in his own heartfelt monologue midway through Nadja, to wit:

She says she loves me. Boy, are they in rough shape. Yet Jim and Lucy clearly have an affection for each other when together, built on a love they believe could last forever. She's not very expressive, barricaded under a steely reserve. He's often too busy drinking all night long with crazy Uncle Van Helsing, perpetually tracking vampires. Clearly, their mess needs to be shaken up a little if they're meant to survive. Most couples would probably do well to have a vampiric brood descend upon them out of the shadows, as it would only serve to remind them of the bonds of friendship, trust, mutual respect and courage which are the foundations of any serious commitment. 2. Jim and Van Helsing may be off having a jolly old time discussing undead 'till they've reached the bottom of the glass, but that's a typical scenario for grown men who still behave as though they were irresponsible children. Women, specifically Nadja, play the more adult games as she embarks upon nights on the town driven by her loyal slave, Renfield (Irish actor Karl Geary). She's first seen picking up an eager young victim in a bar, talking about what a bastard her father is. She needs to simplify her life. She needs to quit smoking. As actress Elina Lowensohn's character said in Hal Hartley's Amateur, and this easily applies to Nadja as well: "I want to be a mover and a shaker." Now that Nadja's father Count Dracula is finally dead (and she torches the ashes to make sure, presided over by befuddled morgue attendant David Lynch!) she can really be free to indulge in her own fancies. This leads her along a strange path, starting when she chooses innocent Lucy as a potential lover based on a barroom encounter. She falls in love quickly, but not well. The pain she feels, as she is quick to inform Lucy (and us), is the pain of fleeting joy. It sounds pretentious, but this informs her desires. She chases taboos with a curious appetite (and her first taste of Lucy's blood is from menstruation, which in an odd way affirms womanhood and acknowledges our culture's inability to talk about such "messy" things). Moving away from Lucy for a spell, she fixes her attention on her distant, hate-filled twin brother Edgar (Jared Harris, later the happy drunk hero of Almereyda's mummy film, The Eternal). If her attraction to Lucy contains the lesbian Eros (and who sounds pretentious now? Me, that's who!), her psychic bond with Edgar is closely linked with incest and her obsessive need to tighten the family unit. At a time when all the lonely people hover in ambivalence, she seeks to reaffirm her cracked notion of family values. Twisted, ain't it? Elina Lowensohn plays Nadja as something of an overgrown teenager, prone to drawn-out philosophical explanations while chain-smoking. Every smile and pout is distinct and scratched clean of artifice, made manifest in Lowensohn's sincere portrayal. She may be a murderess who attempts to steal away the lifeblood of Lucy, who never asked to be taken advantage of or mindfucked, but she does it with a self-deprecating whisper. It's no good to fight something so elemental as the vampire, particularly when she's drawing on sensations lurking discreetly under the surface. Jim might be fucking around on her, so who's to say Lucy wasn't acting appropriately in picking up some stranger in a smoky bar? Be careful what you wish for. They all come out in the half-life. 3. At one point, I was scheduled to interview Michael Almereyda in connection with an article about Renegade Filmmakers (whatever that means). Almereyda respectfully backed out, though he did provide a (lively and enjoyable) fleeting phone call to say he enjoyed the thoughtful questions. Hopefully, at some point we'll be able to reconnect so he can speak for himself, but let's have some fun here. I'll use my own questions to the director as an attempt to spell out some thoughts about Nadja. How about that? Doesn't that sound like a fun idea? OK, maybe not. But I've already committed, and it's too late to turn back now. QUESTION: How did being an art history student affect your cinematic choices over the years? Is it something you always come back to, or is this a moot point? ANSWER: Like fellow New York filmmakers Todd Haynes and Matthew Harrison, Almereyda came from a school of design much more open to experimental film. It's about forms and textures, as opposed to such trifles as plot and coherent structure. Nadja is as simple and straightforward a narrative as Dracula or, more appropriately, Dracula's Daughter (which apparently is the flick Almereyda references scene-for-scene), though the enjoyment is drawn more from a sustained mood of eerie dread through watercolor imagery. Example: One of the more famous shots in Nadja is when the title character seems to be gliding through downtown side streets at a dreamy, deliberate pace -- lighting a cigarette and gazing forlorn at nothing in particular. In the background, running like hell in incredibly slow motion, unable to catch up, are the heroes (Jim and Lucy, to be specific). This has more to do with the logic of dreams, where you can be pushing your legs to move, move, move but you just can't pick up any speed. You'll never be able to catch up to the prize. While Almereyda clearly lifts this image from Jean Cocteau's Orpheus, one has to tip a hat to the filmmaker. If you're gonna steal, why not steal from the masters? Then there are the multiple tracks of bizarre aural configurations, hums, buzzes, blips, ellipses and tones that serve to further disorient the viewer in ways that lure us into some weird, internal blurred-out trance. It's more intoxicating than annoying. The Lynchian use of sound (and I remind the reader that Lynch produced the film with his own money, was a de-facto Godfather, and stood up to bat for Almereyda when few others would) is actually quite beautiful and layered, incorporating a memorably evocative soundtrack (if you like Portishead, that is). QUESTION: Do you consider yourself a New York filmmaker or part of the NY community of filmmakers? ANSWER: This is a stupid question. There is no NYC film community to speak of, though I've heard rumors that they all get together for "high tea" on occasion. I'm not kidding! I don't know about Almereyda, but Ang Lee and Tim Blake Nelson are rumored to literally get together around lunchtime and drink tea. (That's what you have at "high tea," in case you hadn't figured that out already. I think I am overexplaining this point. Let's move on.) I suppose that counts for being a "community," though in fact it's more like an assemblage of independent artists all working on their own thing who occasionally say hello to each other at a film festival. Almereyda only met Todd Haynes while making a documentary called "At Sundance" -- and that was only in the context of an interview. I think they have spoken since, but you get my drift. QUESTION: You use a lot of diverse alternative music in your films. Could you talk about whether or not these affect your editing decisions? Do these help you (and editor Steve Hamilton) come up with a "rhythm" for the films? ANSWER: If I am to speak for Almereyda, I would say the answer is yes. I would love to see this man's record collection, and am grateful he introduced me to Cat Power (who provides the creepy opening rock ballad for The Eternal). He also chooses really great Nick Cave songs, before Nick Cave started to really suck (i.e., the past two or three years). As for how they create the "rhythm" for his films, think about the self-imposed rhythm inherent in the mix-tape, which dictates an entire mood. I'm certain Almereyda and Hamilton cut scenes together using tempo as their guide. There are chase scenes in Nadja that splice together different songs, each corresponding to the nature of the shot. A frenetic bit might offer radical montages of people running, the camera locked down in Dutch angles. Then he'll throw in a long, meandering, luscious image of Elina Lowensohn strolling along West 4th Street (Tower Records glowing behind her), the music shifting into a slower groove. One has everything to do with the other. Music fans will find much to appreciate in Nadja, if they actually like what they're hearing. It's all relative, I suppose. QUESTION: Nadja and Hamlet are cinematic love letters to New York City. How do you choose your locations? ANSWER: If you live in New York, you may enjoy playing "spot the locale" with both these movies. I prefer to think of Almereyda's view of the city as specifically his own, one which transforms NYC into something completely subterranean, foreign, alien, other -- sort of the NYC we see when we fall asleep. Stanley Kubrick achieved a similar effect through a vastly different cinematic approach in Eyes Wide Shut. I haven't really answered this question, though. But it's rude to intercept and interpret someone's love letter (Almereyda's) to someone else (the great city of New York). I feel guilty enough already. QUESTION: Did you enjoy coming up with cinematic references and in-camera effects for Nadja? Much of the imagery was dreamlike. Were you thinking of German Expressionism? ANSWER: References abound. Have fun spotting them. The imagery is dreamlike. Yes, he was probably thinking of German Expressionism. I repeat all this stuff (abundantly stated throughout this review) because now I know what it feels like to be a filmmaker being interviewed. You have to repeat the same old stuff over and over again. It must become frightfully boring. It makes me realize I would much rather talk with Michael Almereyda about his recent trip to Iran than force him to rehash stuff he's sick to death of talking about. Kill me now. QUESTION: In terms of Nadja's narrative, I was often thinking about Tod Browning's Dracula. That movie jumps around quite a bit in terms of location. You do the same thing: we're in New York, then we're under the shadow of the Carpathian mountain. Was this a lift from Dracula, or am I reading too much into this? ANSWER: I am reading too much into this. However, it brings up an interesting point. Almereyda enjoys jumping from one location to another with minimal explanation. This causes the movie to get progressively more confusing as it goes, to the point where the climax (or anti-climax as it were, which I won't give away) becomes a babble of abstractions. Almereyda created a fine safety net for himself in The Eternal, which built up to a very confusing fever-pitch series of incidents that were enormously difficult to follow. How, you ask? The heroes were getting progressively drunker as the movie drew on. Nadja doesn't have that excuse, and thus can seem kinda, well, weird in the final half-hour. The one rock you can hold on to is that Lucy (and probably Jim, too) is becoming increasingly delirious as a result of being soul-sucked by Nadja. It'll all make sense on a second viewing. QUESTION: Have Hal Hartley and/or David Lynch been influential? (Aren't you sick of that question?) ANSWER: Yes, they have been influential. In fact, Michael Almereyda seems to be struggling at certain points to find his own voice. With each movie, he comes one step closer. The use of industrial sound and oddball close-ups are Lynch. The casting of Elina Lowensohn and the great Martin Donovan is a direct steal from Hartley, not to mention the deadpan line delivery, careful compositions, plentiful smoking of cigarettes, and skepticism of wide angle lenses. I hasten to add, these are all smart decisions. QUESTION: Re: The Eternal. Hey, another beautiful shot of the rollercoaster over the opening credits from cinematographer Jim Denault! This begs the question: when working on Nadja and The Eternal, what sort of conversations did you have with Denault about the "look" of the films? What were his feelings about Pixelvision? ANSWER: I really have no idea what sort of conversations Almereyda had with Jim Denault, but I'm more than happy to share my feelings about Pixelvision. It's become something of an Almereyda trademark, really. Not only is there something nostalgic about these images (which resemble broken-up home movies, faded over time and slowly decomposing), it's also curiously detached -- the celluloid image under a blurry microscope. It's... it's just... it's... I mean, I think it's cool. It's a unique form. Boy, do I wish Almereyda were here to answer this question! In Nadja, it can be safely said that the Pixelvision offers the Vampire's Eye View. 4. There are abundant pleasures to be found in Nadja, despite the fact that it's a flat-out mess. Being postmodern can sometimes be read as an excuse to feel "above" the material, and while I'm not saying Almereyda isn't in adoration of his genre (he clearly knows his stuff) he feels the need to inject it with a self-conscious, occasionally smug hipness. It's a little too cool for it's own sake, a little too pleased with the admittedly clever dialogue or the vampire-movie tweaks. Put simply, Almereyda can sometimes come off as the brilliant party guest who says lovely things but keeps elbowing you in the ribs as if to say, "Did you get it? Did you get it?" Stuff like this gives "clever" a bad name. This made me dislike Nadja on my first viewing. Oh, sure, I laughed at the jokes and thought it was a beautiful piece of cinema, but I was put off by how arch, how mannered, how downright confusing it all was. I had zero patience for the Transylvanian climax, where the events are shot in such an experimental way that you can barely tell who is doing what to whom. (It's grown on me, I'll admit. Now, I feel like we already "know" what happens at the end of most vampire movies anyway, so I should sit back and drink in the textures. It's much more pleasing this way, let me tell you.) I might also add that I saw Nadja on a double bill with The Addiction. During Nadja's closing credits (it came first) I muttered, "What a lousy movie." Then, after enduring Ferrara's follies, I acknowledged, "Hey, Nadja really wasn't that bad!" I still wandered around town trashing the movie to my friends, all of whom seemed to find something in the flick that I didn't. The true test of any movie, though, is how you respond to it in the weeks and months and years that follow. Nadja stayed with me -- images, sounds, really kick-ass lines of dialogue ("Face it, Jim -- she's a zombie!"). I rented the movie on video maybe three times a year, and finally last week decided to add it to my collection. It's now sitting on the video rack next to Hal Hartley's Amateur and Todd Haynes' Safe, two other (and, I have to say, much better -- perhaps the best that Hartley and Haynes have made) movies that take a while to adjust to. We're so eager for the quick fix when it comes to cinema these days, when the real treats come from movies that linger around your attic like friendly ghosts, perpetually reminding you they exist. Almereyda has been honing his own blend of modernization, which could be his most exemplary quality as a director. He acknowledged Jan Kott's seminal book, Shakespeare, Our Contemporary as an influence on his energetic present-day Hamlet (2000), which brushed the museum dust off a timeless masterpiece. Arguably his best film (though I'd toss in a vote for his deeply personal 1992 Pixelvision featurette Another Girl, Another Planet), it's an extension of what he'd been doing in The Eternal, his D.H. Lawrence adaptation The Rocking Horse Winner, and, most blatantly, in Nadja. Shaking up cinematic time and space, splicing contemporary sensibilities into old-school technique, and bringing surrealism to the fore, he's bound to break new ground as a 21st Century maverick once his career gets going. If Nadja is to be considered an interesting failure, there's something to be said for the value and substance of broken treasures. Review published 08.17.2001.

|

|

| home | movie reviews | features | sov horror | about | forum |

| This site was previously at flipsidemovies.com from 2000 to 2008. |

|

contact | copyright | privacy | links | sitemap

Flipside Movie Emporium (FlipsideArchive.com)

|